An American Cartoonist in the Palaces of European Painting

My second day in Paris I went to the Louvre. This despite having announced to my companions the night before that I wasn't going to visit its crowded halls again. I came to Europe for the first time in 1999, when I was 25. That trip was mainly to Italy to look at Italian proto-renaissance paintings in places like Florence and Padua and Sansepulcro...

But I made a trip up to Amsterdam as well, and entirely by accident (long story) was able to visit the Prado in Madrid to see practically the entire career of Francisco Goya.

At the very end of the trip I got stranded in Paris for a few days. I had pretty much had my fill of museums by that time, finding that while the continent has a very large number of truly revelatory, beautiful, strange and wonderful pictures of all kinds, it also has an exponentially larger amount of crap. The new economic titans of Europe demanded artifacts of conspicuous-consumption (as new economic titans always do) and apparently painters obliged with piles of ultimately repetitive and uninspired pictures of all sorts. If the U.S. is any different it's only because we came of age at a different time, and employed different means to display our wealth.

Still, the Louvre has its moments. I love the rooms with the giant Delacroix's and Gericault's and David's – the giant Hollywood mega-blockbusters of their day...

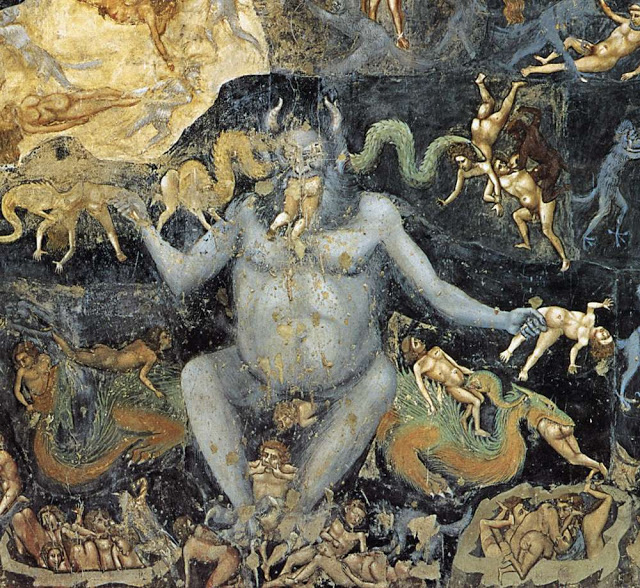

But the picture that summed up the arc of Western painting for my tired eyes in 1999, was this one:

When it stopped me in my tracks again last week I felt the same amused disdain, but it was mixed now with a certain nostalgia and the goofy fondness one has for someone you used to hate in high school who turns out to actually be kind of fun to talk to. I'm sure this guy, in his day could have had me burned alive for looking at him the wrong way, and yet here he is, frozen for all eternity, with that haircut. But this painting has stuck in my mind for the last 14 years because it completes a perfect half circle. The rising merchants (and, yes, crime bosses) of the aforementioned Italian cities began the tracing of this curve by hiring a new crop of incredibly inventive and ambitious young painters to try and encapsulate the mythology and world view that gave their lives and culture meaning in their own eyes. They did it in ways no one had ever imagined before. But for these patrons to have themselves depicted other than in supplication and extreme humility (the guy in purple, below, handing a new chapel over to The Virgin Mary and her friends) was not even a question, they were really and truly trying to get into Heaven by commissioning these works:

(and also: out of Hell)

By the time we get to the fellow with the flowing locks, however, the relationship is completely inversed. Suddenly it is the gods and angels that wait, their clothes all but sliding off their bodies, at the pleasure of these masters of a newly global universe. Images like the Last Judgement above stop getting affixed to Church walls at about the same time that actual horrors almost as fantastic are being enacted in the mines and plantations of the New World. Eventually images like this make their way little by little into new imaging technologies like printed books and eventually political cartoons (see Goya, above), but the spotlight of visual culture has decidedly moved on.

Of course there are a small number of really wonderful, humbler pictures at the Louvre. Painters, of course, continued to find ways of describing the strangeness, bitterness and beauty of the world whatever the economics happened to be. Here's a portrait of a flute player, blind in one eye:

Of that strangeness and beauty I found a bunch the next day at Le Musee de la Chasse, and much of all three qualities at the Musee de la Beaux Artes yesterday in Brussels. That place was a revelation. So avoid this URL for a few days if you're sick of dusty old paintings.

But I made a trip up to Amsterdam as well, and entirely by accident (long story) was able to visit the Prado in Madrid to see practically the entire career of Francisco Goya.

At the very end of the trip I got stranded in Paris for a few days. I had pretty much had my fill of museums by that time, finding that while the continent has a very large number of truly revelatory, beautiful, strange and wonderful pictures of all kinds, it also has an exponentially larger amount of crap. The new economic titans of Europe demanded artifacts of conspicuous-consumption (as new economic titans always do) and apparently painters obliged with piles of ultimately repetitive and uninspired pictures of all sorts. If the U.S. is any different it's only because we came of age at a different time, and employed different means to display our wealth.

Still, the Louvre has its moments. I love the rooms with the giant Delacroix's and Gericault's and David's – the giant Hollywood mega-blockbusters of their day...

But the picture that summed up the arc of Western painting for my tired eyes in 1999, was this one:

(and also: out of Hell)

Of course there are a small number of really wonderful, humbler pictures at the Louvre. Painters, of course, continued to find ways of describing the strangeness, bitterness and beauty of the world whatever the economics happened to be. Here's a portrait of a flute player, blind in one eye: