Geneviève Castrée: Complete Works,

A couple of weeks ago Drawn & Quarterly published the long awaited Complete Works of Geneviève Castrée. As far as I’m concerned it’s the book of the decade. You should get one. Apropos of the occasion I figured I would post the piece I wrote after she died in 2016, that ran at The Comics Journal. I can’t sum up who she was any better than I did then, except maybe to re-iterate that her work was amazing, under-appreciated and very much worth your time and attention.

As you’ll read in the piece below, Geneviève was someone who sent exquisite, unexpected gifts in the mail. I happen to have an extra copy of the book, and so I’m going to give it away in the mail. Anyone who buys anything from my web-shop in the next ten days (until December 8th at 11:59), or tags a friend in the comments on my instagram post about Geneviève in that time will be entered. Do both and you’ll get entered twice. Sorry, I don’t have any homemade jam.

Here’s the piece from TCJ:

REMEMBERING GENEVIÈVE

Author’s note: The first thing I need to say about Geneviève Castrée – because it mattered to her very much – is how to pronounce her name, or at least how she cajoled me into saying it with my clumsy American-English tongue: it’s zhun-vee-ehv. Not zhon-vee-ehv, and definitely not Jenna-veev. Geneviève. Okay, now we can begin.

I became friends with Geneviève Castrée after her husband, Phil, wrote me a letter in 2006. He wrote after the two of them had been stuck in their car waiting in a line to board a ferry shortly after picking up a copy of my book Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow, which was just out at the time. Phil said they had read it together, sitting there in their car, and it had affected them very much. So he wanted to write and say thanks. He sent me a record, too and so I wrote back to say thanks myself, or, I guess, “you’re welcome” or some other slightly awkward thing, and maybe I sent a minicomic or something as well, in return. Later I got a follow up from Geneviève, and from there we struck up a correspondence. Little packages of books or records or homemade jam would arrive with a small drawing and a letter in her small, lovely, unmistakeable cursive handwriting letting me know a few details of her week, or her work, or her cats. She was a giver of gifts of all kinds. It was in her nature.

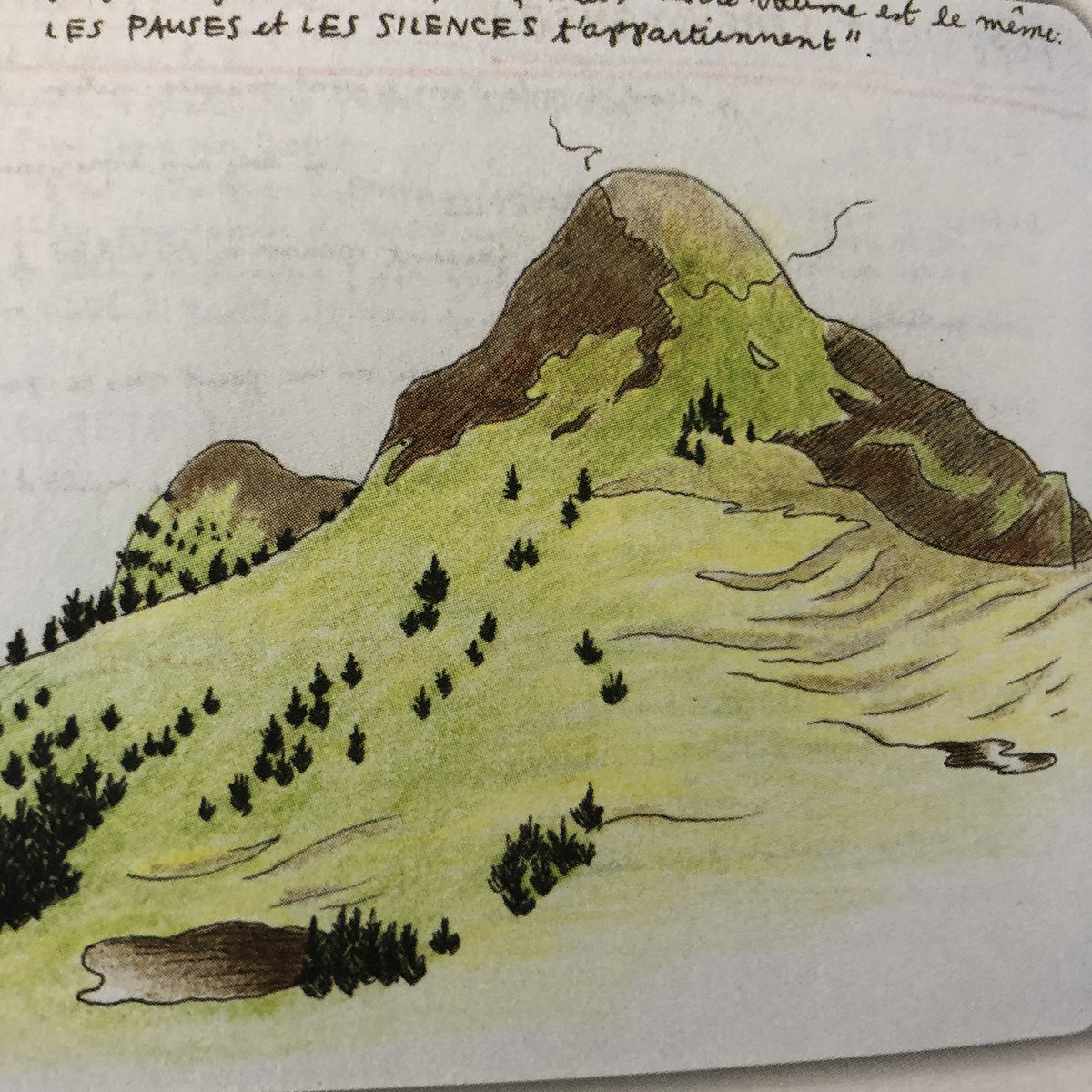

That correspondence meant a lot to me because I was already aware of her work, and an acknowledgement from her felt profound. I was in awe of Geneviève’s work. I remember her as a sort of mysterious figure on the outskirts of American indy comics. There had been a beautiful little red book in French that got passed around to wide eyes, and then all of a sudden there was Pamplemoussi, a screenprint-and-offset 12” square book-and-record that seemed to emerge out of nowhere. And it wasn’t just impressive as an object… it was really good. By the nature of alternative comics you usually get to see artists’ early awkward stages, where they are muddling through and figuring themselves out. Geneviève was young enough that even if we had been keeping up with French-Canadian comics, which we weren’t, if we’d blinked we’d have missed her formative years anyway. I followed her work where I could after that though it was never easy to find unless you knew someone. But then she did a full color piece for Drawn & Quarterly’s Showcase in which she reinterpreted elements of Hergè’s Tintin in Tibet as a kind of autobiographical love poem. When the mini-history is written of cartoonists interpreting Tintin, that piece will be at the top. It was perfect and strange and heartbreakingly beautiful. She was an uncompromising feminist who nevertheless had an uncomplicated love and enthusiasm for the the peculiarly almost entirely male world of Hergè. The last time I visited her in Anacortes she found me perusing her collection of Tintin books and proudly told me that as a child she had studied for and entered a competition of knowledge about the Belgian reporter’s adventures. And won.

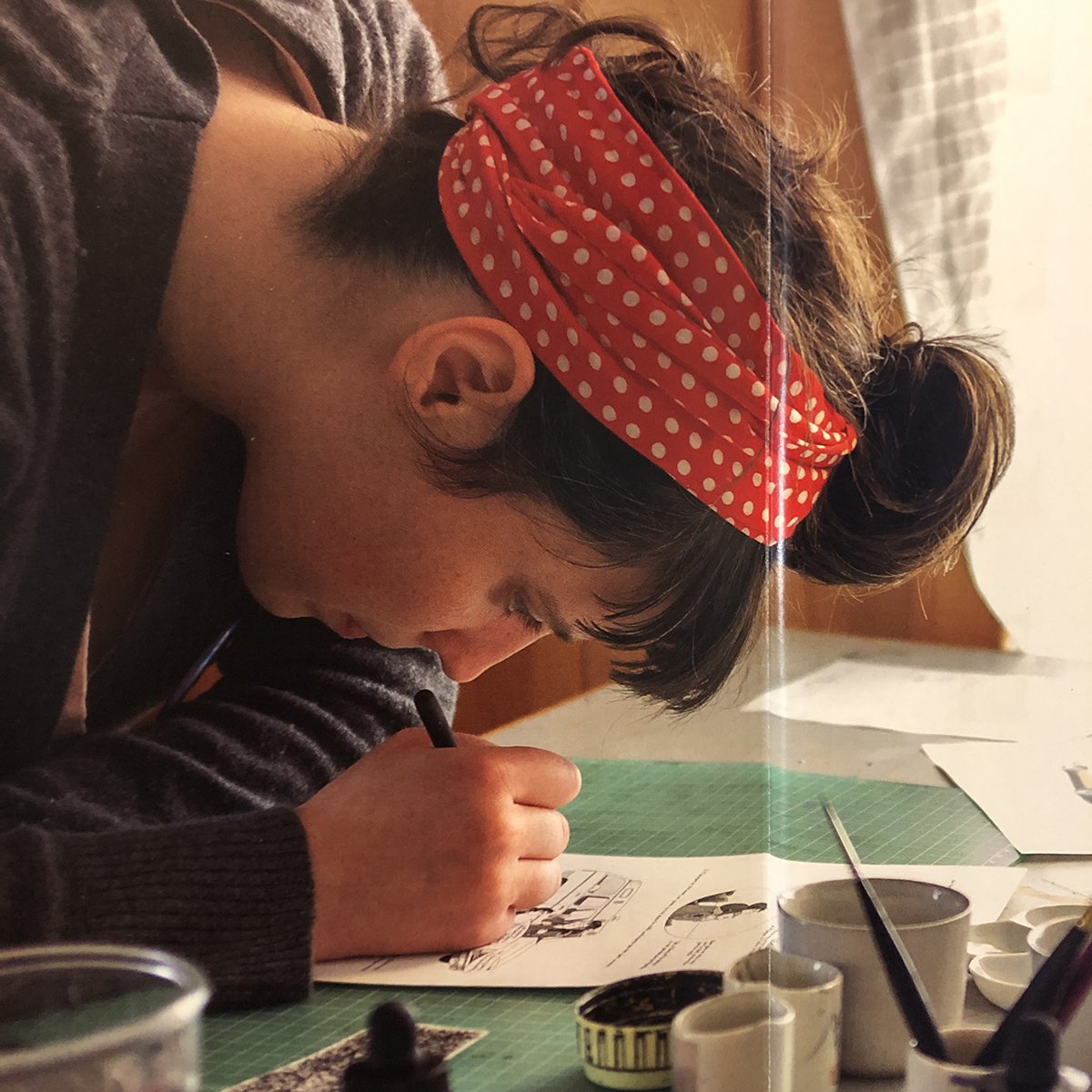

Geneviève was extraordinarily productive. The list of small and large books and records (and books-and-records) she made is much longer than her reputation might imply. Not to mention her paintings and the art shows and music festivals she organized. And the jam she made.

She should have been better known as an artist. She was mostly a self-publisher and willfully flouted the boundaries between her chosen fields. Her books were records and vice versa – in a way that probably would have confused many retailers in both worlds even if they had come across them. But I think it delighted her more to give her books and records away as gifts than to go out of her way to solicit them for review or track down stores to sell them to. Self-publishing was a political choice at least in part, but it seemed to me that it was simply in her nature, as well. As a giver of gifts. Which is not to say the sales numbers accompanying a particularly small royalty check was any less painful for her than any of the rest of us.

Our paths crossed now and then in person, as well as on paper or over the air. She didn’t go to festivals much in the US, but I was able to invite her to a comics residency in Minneapolis in 2013 – PFC4, and we shared a little farmhouse in Angoulême one year when we were both guests. The late-night walks between the festival and the farmhouse meant a lot to me. Away from the chaos and noise of the tents, ambling through centuries-old streets and past farmers’ fields, under the stars, we hashed out our fears and hopes for the future. Both of us were at promising moments in our careers that winter and straddling different kinds of cusps in our personal lives. She’d had a brief, unexpected brush with the idea of having children, and was wrestling then with whether to try to become a mother. About a year later she let me know she was pregnant. Having wrestled with the idea of motherhood, once she made her decision and had a daughter she was as purely delighted as any mother I’ve ever known.

Geneviève was an extremely helpful counsellor to me about my own work, something rare and precious in comics. Around the time she was finishing the autobiography of her complicated childhood, Susceptible, I was re-working and collecting my own memoir-ish The End. Our conversations about the complex interplay of one’s life and one’s work helped shape my own book in very concrete ways and continues to inform how I think about autobiographical storytelling.

What else? How do you sum up a person and friendship that has shaped you? She and Phil put on the best music festival I’ve ever been to, The Unknown. I aspire to make drawings half as exquisite, beautiful and strange as Geneviève’s. I want my house to be half as fun to explore. She was thoughtful, kind and direct in conversation, she was opinionated and loyal. When my French publisher decided to keep my book’s title, Big Questions, in English on its French language edition she spent an hour breaking down for me the cultural complexities of the decision. As a Québécoise she didn’t like it, and wanted me to understand why it mattered.

So Geneviève was all these things. And she should have had fifty more years to play out her own particular genius on this planet – as a musician, storyteller, mother, wife, and friend.

Our story took us full circle. The book of mine she and Phil had read together all those years ago was the story of my partner at the time, Cheryl, and her own battle with cancer and death at a ridiculously early age. That’s what our friendship started with. A little over a year ago, shortly after her own diagnosis Geneviève gave me a call. Perhaps in part she wanted to talk to me as a friend, but she also wanted to hear from me as someone who might actually understand what she was facing. I welcomed her questions and was eager to help in whatever way I could in the face of something so monumentally terrifying and unfair. And so I did. But there was a dark subtext to that conversation that we both sensed, I think — Cheryl had died. Geneviève wasn’t planning on going that way. She was determined to fight, however impossible the odds, to move toward health in any way she could figure. After that first conversation I avoided openly comparing her situation to Cheryl’s. She asked different questions. I hoped she would recover, too. I desperately wanted the parallel to end at diagnosis and treatment.

Last week, she got in touch and asked about Cheryl again. There was no avoiding that darkness anymore. Geneviève’s doctors had run out of options. She’d entered hospice. And she wanted to know what I thought. What choices had Cheryl and I made? What would I do differently? She was trying to figure out how she should die.

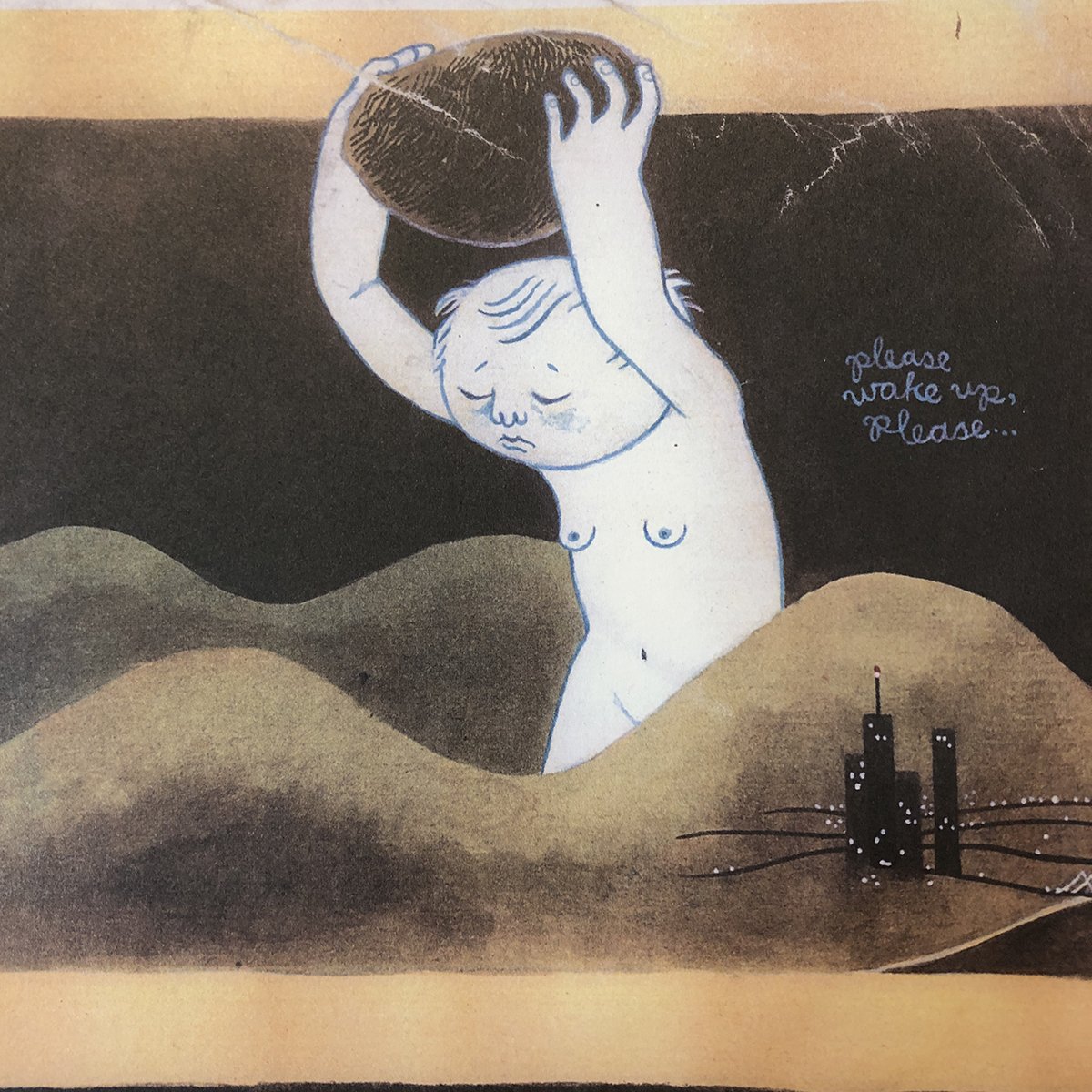

Earlier that same week, though, she sent me another kind of message: images of a whole mess of exquisite small drawings spilled out in her studio. One, still in progress, was a jewel-like rendition of a mother and daughter scribbling together on paper with markers, radiantly smiling in red stripes. The darkness was there, terrifying, inevitable. And Geneviève was making beautiful, inspiring drawings until the end.

A postscript to the above that I guess would be relevant is to say that the drawing above was part of a children’s book she was working on when she died. It was about a mother who was stuck inside a bubble. It was mostly done, except for several character’s hair and a few other details, and the bubbles. I helped finish the drawings and did the lettering to finish it. That book is also available from D&Q, and it’s lovely and, as you might expect, heartbreaking.

So, yeah. Geneviève is gone. But her work is alive. Thanks to D&Q and Phil Elverum for that.