"IT ALMOST FEELS LIKE YOU COULD SPEND THE REST OF YOUR LIFE DOING THIS"

A couple of months ago it dawned on me that 2021 is the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Big Questions collection. My days have been pretty well occupied with new work this year (mostly Tongues #5, but also some book covers I’m designing for hire), which is as it should be, but that has made it a little hard to find the time and mental bandwidth to mark the moment properly. But the book was an milestone in my own life and career as a cartoonist in more ways than I can easily count, and it appears, even ten years later, that I’m not the only one who still cares, that the book is still finding its own way in the world. Most notably the book has just been translated into Italian by the good people at Eris Edizioni, its fifth international edition – so apparently someone out in the world still thinks there’s an audience for a six hundred-page book about talking birds.

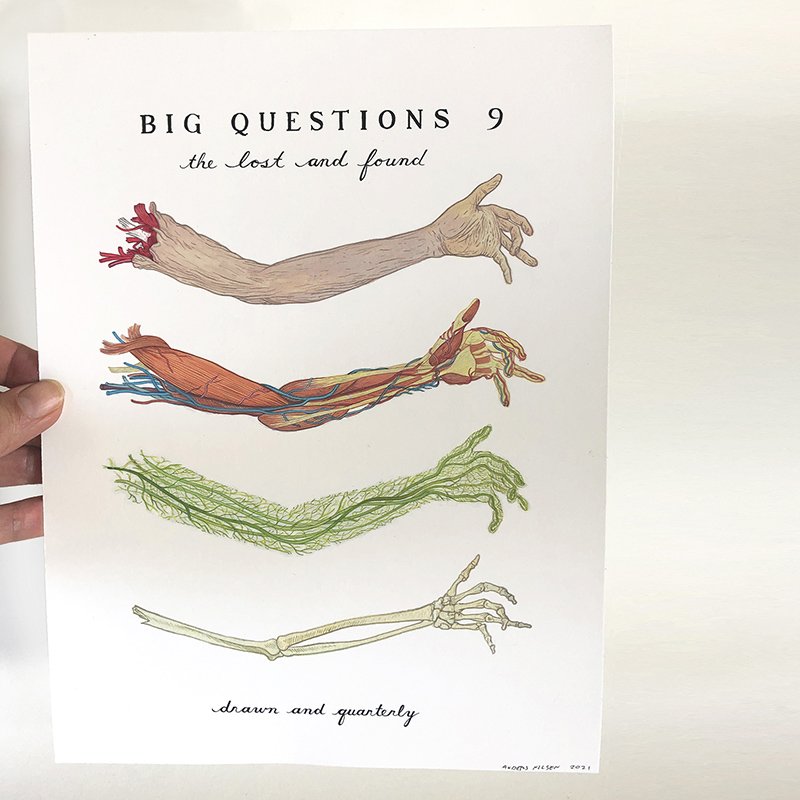

So I’m going to lay down a marker, and to record a few thoughts and memories about the book’s origins here, somewhere in the vicinity of the tenth anniversary. I also put together a few items to give away and sell in the shop to commemorate the occasion, including a new shirt, a print and a postcard set (scroll to the end of this post, or just click over to the webstore).

The first glimpses of what would become Big Questions surfaced in the summer of my senior year at the University of New Mexico during a week-long workshop at the D.H. Lawrence Ranch in Los Alamos. The workshop was led by my painting professor, Marjory Amdur and was generally concerned with the generation of ideas and imagery and with learning not to be too precious about your work. For one exercise she had each participant bring to class a single object that felt important to us and assemble a stack of sixty sheets of paper. I brought a little plastic toy soldier, of the kind I regularly played with as a kid, creating giant scenes of battle on the dining-room table, or spread across the floor of my room.

As the exercise began we were given sixty seconds to draw the object, then told to switch to a new piece of paper and to draw it again. Then again, and again, and again – sixty times for an hour. The idea (unstated at the outset) was that whatever your usual, habitual way of drawing might be, you’d soon tire of it and try something else, and then something else and maybe come up with an entirely new and unexpected way of working.

I pretty quickly moved from drawing the little figure directly to doing a series of riffs on the theme of militarism and violence… and then, as I hit that wall of repetitiveness we were meant to tire of, the individual sheets of paper became one-minute panels in a very crudely drawn comic. A soldier collapses and dies and sinks into the earth, some birds come down and sit on his boot, a plane crashes, the birds fly away, and a figure emerges from the wreck.

After that the narrative, such as it was, went in some other directions. I remember a distinctly new feeling of exhilaration at watching these ideas bubble up and out onto paper (there actually was one person in the class who had taken the idea extremely literally and done the exact same drawing sixty times, only occasionally varying the color of her pencil – she was extremely annoyed at the end, if I remember right). And then the hour was up and it was over. I tapped three nails into the stack of paper on its left side, making a crude binding, turning the pile of paper into a sort of book. The workshop wrapped up a few days later and we all went home. It wasn’t very long before the birds started to appear in my sketchbooks.

When Fall semester came I went back to work on the collage and sculpture and installation art that constituted my senior thesis show – one highlight was going to a shooting range and blowing away a wooden folding chair for the show with my advisor and his shotgun, then roughly reconstructing it for the show’s centerpiece. December came, I put up my show and graduated. I hung around Albuquerque for several months, working on another exhibition of that work out of town and waiting for my friend Adam to graduate so we could move to San Francisco that June. Being banished by graduation from the art building’s studios, my sketchbook became the main outlet for my work. And little by little the collages and endless writing in those journals began to be infiltrated by short comic strips about those little birds from the exercise in Los Alamos.

They’d begun talking to one another, and developed names, mostly lifted from my grandparents and great aunts and uncles. Friendly, familiar, solid names a couple generations removed: Helen, Louis, Thelma, Charlotte. I had one great uncle, my aunt Thelma’s husband, who I had known only as “Bud”, which didn’t feel quite right for the birds. So I asked my mother what his real, given name was. It was Algernon.

More time passed. I spent one year in San Francisco, then applied to grad school in Chicago and moved from San Francisco back to Minneapolis, where I’d grown up, to stay with my mother for a year, save money for school and do some traveling. Minneapolis felt about a thousand miles away from art school and anything like an “art world” where people make “installations”. But poking around in my sketchbooks I realized I had enough little bird strips in various journals to photocopy some of the good ones and turn the results into a zine. One of the strips was called “Big Questions”, which seemed like a workable, ironic-but-friendly sort of title for the whole little pamphlet, so I put that on the front.

The proprietor of a local comic shop called Big Brain agreed to put them on the shelf. I gave some to friends at the co-op I worked at and they actually laughed out loud at some of the jokes. Which made an impression on me. No one had had an actual involuntary physical reaction to the installations, or to my paintings, they just stood there and looked at them. And making the zine had been fun, regardless. So I decided to do a second one. I didn’t have quite enough decent material left in the sketchbooks, so I had to come up with something new. On purpose. Which was novel.

One day while walking up the alley on my way home from the co-op, I was listening to a cassette tape of a band called June of ‘44, a song called Sanctioned in a Birdcage. The song is a sort of angry poetic lament about the fraught relationship of human culture and civilization to nature, symbolized by, in particular, birds and their trees. They were a great band, you should listen to them. Anyway, as I listened, an image popped into my head of a bird flying in circles looking for his tree, and finding it has been cut down. I went inside and put it down on paper. That sequence became the cover of the second issue.

Some of the other strips I made for it involved two other birds having a sort of naive, detached conversation about philosophy, roughly developing a theme of the first issue. And then at the end, this bird from the cover who appears to be experiencing an actual tragedy, Algernon, arrives and asks them if they’ve seen his mate. I had suddenly gone from having birds with names and the beginnings of personalities to having a story. Which felt slightly magical… like something a person might, possibly, maybe… spend a whole lifetime exploring.

That March I drove with my friend Emily to New York. She was starting graduate school in English Literature at NYU, and I was getting on a plane to Europe to look at proto-renaissance painting. Somewhere along the way, for some reason that I don’t remember she read me the poem Spring, by Edna St. Vincent Millay. The last line compares the month of April to “an idiot, babbling, strewing flowers”. And something about that image struck me. An Idiot. I did a drawing of it in the sketchbook I had brought along. The first drawing of The Idiot. Strewing flowers. A human character to drop in the path of the birds, maybe.

It’s hard to remember exactly what made me decide to go to Italy to look at old painting, In part I think it was a sort of familial inferiority complex about travel. My parents had spent two transformative years in the Peace Corps in Ethiopia in the late sixties, my sister had spent time in Nicaragua and Brazil, and all I had mustered was university in New Mexico. I felt a need to see more of the world, and looking at old painting sounded plausible enough as a reason. I don’t remember if I understood the trip as a pilgrimage – to stand in the presence of the beginnings of western painting and visual storytelling. But that’s how I was starting to see it by the time I got on the plane to fly home. The work of Giotto and Masaccio and Fra Angelico, much of which was quite clearly made up of images in sequence, telling a story, (“comics”, arguably… if that’s the sort of argument you like having) felt deeply familiar in a way that I hadn’t expected. I’d seen bits of these artists’ work in slide lectures in dim lecture halls, and in books, but standing in front of the work was completely different. For me it was revelatory.

You could see the hand of the artist in the brush strokes dragging pigment through six hundred year old plaster. And it was a time before artists had started getting distracted by technical concerns like perspective and anatomy and getting the lighting just right. The figures were simplified, iconic – they were cartoons, basically – in something very close to a modern sense. They were doing at a very high level in the 1400s, exactly what I wanted to be doing with my life in – artists trying to tell engaging, strange, meaningful stories about the world in pictures.

Spending time with this work from the far past helped me get much more comfortable with the path I was beginning to walk down. It helped me fully absorb that a turn away from the art of contemporary high culture, away from the concerns of galleries and museums, wealthy collectors and jargon-laden art magazines did not have to be a turn away from the deepest roots of art-making. Quite the opposite. Making comics and telling stories, which I seemed so powerfully drawn to do, was a direct embrace of those roots, of image, of story, of the all the most vital aspects of the human meaning-making mind.

It gave me the final nudge to fully embrace comics and storytelling and to step away from the installation art and stand-alone painting that I’d been holding onto without very much good reason since finishing undergrad. When I returned to the U.S., and started grad school in Chicago that Fall I had fully embraced making comics and set about seeing where these birds and this idiot and that crashed airplane might take me.

• • • • • • •

The making of the book that followed is a whole other set of stories. The full book ended up taking roughly twelve years from that point to finish. I took breaks now and then to do other projects – I put out four other books (depending on how you count) and a number of unrelated short stories and mini-comics before it was done. But that initial sense of endless possibility carried through. And was always readily available when I would come back to the birds. The book very clearly reflects the fact that I was learning how to make comics as I went. Arguably it is a flaw – the drawing style changes at least twice in the first half of the story, my use of panels shifts a few times as well. And I am simply better at every aspect of the medium at the end than I was at the beginning. But that’s also what makes the book what it is. It’s part of its character and the experience of taking it in. Part of the books own internal metaphysics, maybe.

So, happy anniversary. And now back to the present. I promised items.

There’s a newly designed t-shirt, a set of postcards, a print, a bunch of bookmarks, and a button. And through November the print will actually come free with any copy of Big Questions (hardcover or soft) ordered from the shop. So, like, if you already have a copy of the book for yourself, grab one for a friend for the holidays, and swipe that print for yourself. And all orders in the webshop for the rest of the year (or until I’m all out of everything) will come with a bookmark (one of five, featuring all the characters). Orders over $20 will come with a button. So yeah, tons of swag. We’re celebrating. Ten years.